CONVIVIALITY IN PRACTICE:

Field research, screenings and 2-day convivial workshop in CAPE TOWN, South Africa

October 9-13, 2023

Research Itinerary

Field research

9 October 2023

Cape Town

Castle of Good Hope

Car/Castle and Darling Streets, Cape Town

District Six Museum

25A Buitenkant Street, Cape Town

A4 Arts Foundation

23 Buitenkant Street, District Six, Cape Town

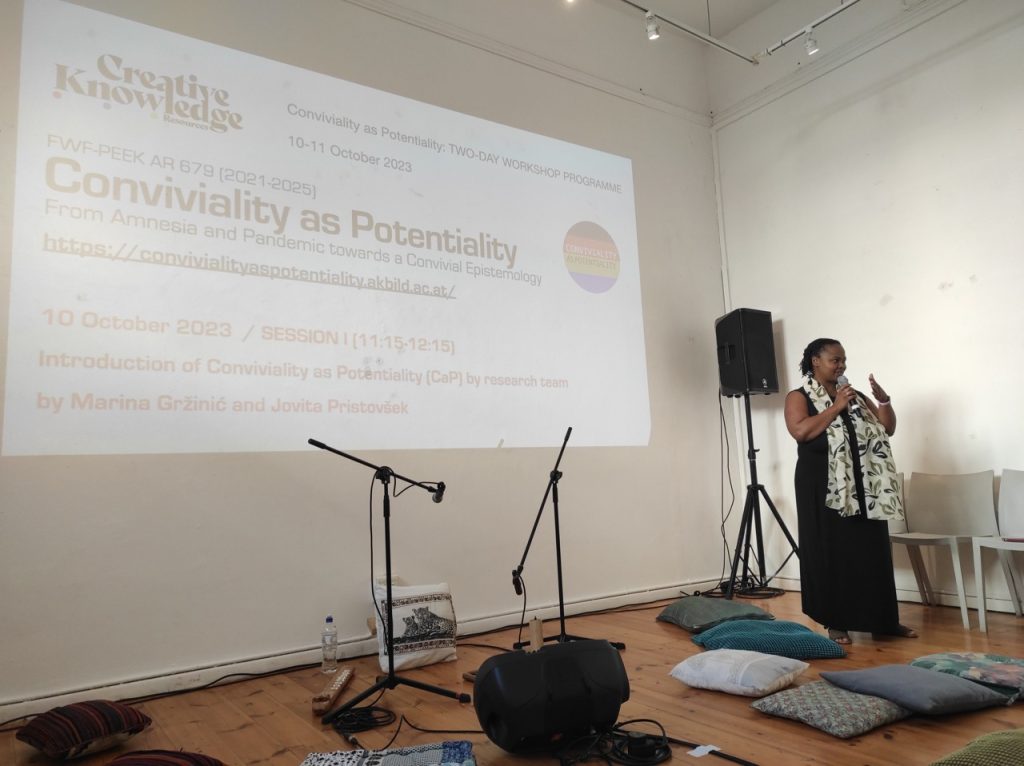

Convivial workshop

10-11 October 2023

at Ritchie Studio, Michaelis School of Fine Arts, University of Cape Town

Part 1: Tuesday, October 10, 2023

10:00 – Introduction by Nomusa Makhubu

10:15 – Participatory WORKSHOP focusing on breath+voice+sound+body (Sisonke Papu)

11:15 – lntroduction of Conviviality as Potentiality (CaP) by research team, Marina Gržinić and Jovita Pristovšek

12:15 – 2pm BREAK

14:00 – Panel Discussion: Practicing Conviviality

Discussants: Jordan Pieters, Nkone Chaka, Thania Petersen, Sisonke Papu, facilitated by Kim Reynollds

Panel reflects on challenges and possibilities of conviviality

15:00 – Inputs from Vienna research team, On Theory and Practice, conviviality and short films.

Screening materials from conviviality in practice.

Part 2: Wednesday, October 11, 2023

10:00 – Discussion, reflections, feedback and analysis of previous day’s screenings: A conclusive discussion on the questions which the Conviviality as Potentiality team have formulated.

11:00 – Panel Discussion: On Conviviality and What is Just

Discussants: Goitsione Mokou, Hannah Mutanda Kadima Kaniki, Darion Adams Facilitated by Mpho Ndaba.

Discussants reflect on their own work and the question ofjustice in relation to conviviality.

12:15 – 2pm LUNCH

2 – 4pm: Interactive closing participatory workshop II by Sisonke Papu

5pm DINNER@ PERSIAN PEACOCK

176 Upper Buitenkant St, Vredehoek, Cape Town

Film Screening: 7 – 8.30pm

Insurgent Flows. Trans*Decolonial and Black Marxist Futures. Experimental-documentary video film: 90min Authors: Marina Gržinić and Tjasa Kancler

Field research

12 October 2023

Cape Town

Desmond and Leah Tutu Foundation

The Old Granary Building, Buitekant St, District Six, Cape Town

16 on Lerotholi

16 Lerotholi Avenue Langa, Cape Town

Norval Foundation

4 Steenberg Road, Tokai, Cape Town

Southern Guild

Artist walkabout with Kamyar Bineshtarigh of his solo exhibition 9 Hopkins

Zietz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa

Silo District, V&A Waterfront, Cape Town

- Unathi Mkhonto: ‘To Let’: a Zietz MOCAA Atelier, residency programme

- Mary Evans: ‘Gilt’: a solo exhibition by Nigerian-born, British artist Mary Evans.

- Seismography of Struggle: Towards a Global History of Critical and Cultural Journals, curated by Zahia Rahmani

- Past Disquiet, curated by Kristine Khouri & Rasha Salti

Field research

13 October 2023

Cape Town

Table Mountain with local researchers.

Research through the markers of settler colonialism in Cape Town.

Analysis

November 2023

by Marina Gržinić

Contexts: Case 1, Cape Town, South Africa

The case study was conducted in situ by two members of the research team, Marina Gržinić and Jovita Pristovšek. We have so far published a visual diary of the in-situ phases of the research and workshop. Immediately after the research trip, we also published a diary with impressions and reflections.

A contextual analysis with reference to many sources reveals methods of counter-learning. It is on these three levels (visual diary, diary and contextual account) that we will use as the base to reread the transcripts of the presentations and panel discussions and (self-)reflections as well as the conversations and tours within the violent colonial history of Cape Town and beyond.

internationalization of the topic: from Europe to the global world: from North to South

We travelled to Cape Town and South Africa after years of researching colonialism in Europe using the example of the Belgian Congo. We asked ourselves what forms of conviviality can be found in the African context and, more importantly, whether it is possible to envisage a post-apartheid conviviality in South Africa.

against apartheid and the white supremacist power regime

The research trip to Cape Town is related to our long-standing research on colonialism and coloniality. The form of colonialism that we identify in our analysis of the Cape Town case is settler colonialism. This is the main form that has historically been practiced along with apartheid in South Africa. Apartheid, this toxic, exploitative, extractivist and ultimate form of segregation and subjugation, is a form of structural racism that is accompanied by persistent forms of racialization. Apartheid was the persistent and violent colonization of a territory by colonial settlers.

Post-apartheid also goes hand in hand with the transformation of the dominant white power position in the apartheid regime into today’s white minority, which still exercises forms of segregation, discrimination and power. These forms are gated communities, the international multinational reproduction of capital and labor, the extractivist logic of Cape Town’s social, cultural and institutional architecture, and so on. What we see as post-apartheid capitalism is a system of reproducing inequality, race, gender and class, with ongoing oppressions on a global and less overt level.

transvisual political studies and cooperation with universities

This fieldwork is possible thanks to the generous program developed by our partners in Cape Town, the university of Cape Town and Professor Nomusa Makhubu, Creative Knowledge Resources, and all those who participated in the program.

The second phase is Professor Maukhubu’s visit to Vienna (2024) where she will work with the students and partners as well as the Austrian public on the same themes of conviviality and beyond. Finally, the project will be presented in a book together with other research cases in Australia, Israel and Europe (Sweden and Austria).

Research field: Disentangling and unlearning

The Castle at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa’s version of the American Pentagon

Cape Town was founded in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company or Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) as a refreshment station to supply the ships of the Dutch East India Company with food on their way to Asia and to offer the sailors a place to rest. The decisive factor for the settlement of the town in Table Bay was the availability of fresh water, which was difficult to find in other areas. The Western Cape region, which includes Table Bay (where the modern city of Cape Town is located), was inhabited by Khoikhoi who used it seasonally as grazing land for their cattle. When European ships landed on the shores of Table Bay, they came into contact with the Khoikhoi. It was only after the gradual dispossession of the local Khoikhoi pastoralists by the early Dutch settlers that the area was opened up for European settlement (see South African History Online, n.d., “The Arrival of Jan Van Riebeeck in the Cape – 6 April 1652”).

The prior history

The past was in connection to the year 1480, when Portuguese ships landed on the coast of the west coast of Africa. Bartholomeu Dias explored the continent further south and unknowingly sailed around the Cape in 1488. Dias called the cape the Cape of Storms, but John II, the King of Portugal, renamed it the Cape of Good Hope. The name expressed the king’s optimism that a sea trade route to India could be opened through the Cape. In 1497, Vasco da Gama and later Ferdinand Magellan sailed around the Cape on their way to India. The mapping of the African coast by explorers and the creation of an alternative trade route by sea between Europe and Asia accelerated the colonization of the Cape. The conflicts with the Khoikhoi caused the Portuguese to avoid the Table Bay area.

This changed in the early 17th century when the Dutch and English established trading companies to challenge Portuguese and Spanish domination of European trade with Asia. In 1600, the East India Company was founded by the British, followed by the founding of the Dutch East India Company in the Netherlands in 1602. The Dutch East India Company acted as the representative of the Dutch government in Asia and expanded Dutch influence by seizing land, expanding trade routes and establishing trading outposts. Between 1610 and 1669, for example, the Dutch East India Company took possession of colonies in Batavia, Indonesia, Colombo in Sri Lanka, Malabar in India, Makassar and the Dutch East Indies.

By the middle of the 17th century, the Dutch had replaced the Portuguese and Spanish trading networks and established their own. By 1620, the Dutch East India Company was the largest company in Europe trading cotton and silk from India and China. In the 1600s, both the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company increasingly used the Cape as a staging post for their maritime trade, occasionally pitching tents on the coast to trade with the Khoikhoi (see South African History Online, n.d., “The Dutch Settlement”).

During the same period, the area around Table Bay and Robben Island was increasingly used by the Dutch and British. In 1611, for example, Dutch sailors were shipwrecked on Robben Island. In 1615, ten British prisoners were unloaded on Robben Island and in 1648 the Dutch unloaded mutineers on the shores of Table Bay.

In 1651, the Dutch East India Company gave the order to establish a provisioning station at the Cape to supply the Dutch East India Company ships with fresh vegetables, fruit and meat on their way to the East Indies. Jan van Riebeeck was hired by the Dutch East India Company on a five-year contract to build the rations station. Van Riebeeck was also commissioned to build a fort for defense against the Khoikhoi and other European competitors.

In December 1651, Van Riebeeck left the Netherlands for the Cape of Good Hope on board the Drommedaris, accompanied by two other ships, which arrived at the Cape on April 6, 1652. A mud and timber construction was erected in Table Bay for protection and defense. In the same year, the Dutch East India Company granted the men permission to own land, build farms and improve the food supply. As early as 1655, some of the company’s employees planted their own vegetable gardens near the castle.

Despite these agricultural efforts, the Cape settlement remained largely dependent on food supplies from Amsterdam, in 1654, for example, fully. The order to establish a permanent settlement was therefore an attempt by the Dutch to exclude the British, with whom they were at war. In 1795, the British, who were at war with France, invaded the Cape Peninsula from False Bay and took over the Cape (including Cape Town) from the Dutch until the colony was returned to the Dutch in 1803. When war broke out again between the British and French in 1806, the British occupied the Cape Colony permanently.

The Castle of Good Hope

The Castle of Good Hope at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa’s version of the American Pentagon, is a fortress in the shape of a five-pointed star and the oldest surviving colonial building in South Africa, built by the DEIC between 1666 and 1679. It replaced an older fort called Fort de Goede Hoop, which was built from mud and wood by Jan van Riebeeck, the Cape’s first commander, who arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. In 1936, the fort was declared a historical monument (now a provincial monument) and after restoration work in the 1980s, it is considered the best-preserved example of a Dutch East India Company fort. The fortress was partly built using slave labor. The Dutch East India Company was unsure of the size of the local population and therefore feared an uprising if they enslaved them. Instead, they brought in up to 60,000 slaves from Madagascar, Mozambique, the Dutch East Indies and India. The work was frequently interrupted because the Dutch East India Company was unwilling to spend money on the project. On April 26, 1679, the five bastions were named after the principal titles of William III of Orange-Nassau: Leerdam in the west, with Buuren, Katzenellenbogen, Nassau and Oranje in a clockwise direction. The names of these bastions were used as street names in suburbs in various provinces, but most notably in Cape Town, such as Stellenberg, Bellville.

decolonial approach to maximum violence

The apartheid system of racial segregation

The apartheid system of racial segregation was enshrined in law in South Africa in 1948 when the country was officially divided into four racial groups: Whites, Blacks, Indians and Coloreds (or people of mixed race or non-whites who did not fit into the other non-white categories). “Homelands” were created for blacks, and if they lived outside the homelands with whites, non-whites were not allowed to vote and had separate schools and hospitals and even beaches to swim or park benches to sit on. It was a crime for a white person to have a sexual relationship with a person of another race, but the person of the other race, not the white person, was prosecuted. The system of apartheid ended when President Nelson Mandela came to power in 1994 (New Learning Online, n.d.).

District Six

District Six (Afrikaans Distrik Ses) is a former inner-city residential area in Cape Town. In the 1970s, more than 60,000 of its residents were forcibly resettled by the apartheid regime. The area of District Six is now partly divided between the suburbs of Walmer Estate, Zonnebloem and Lower Vrede, while the rest is generally undeveloped land.

The area was designated as the Sixth Municipality of Cape Town in 1966. The area began to grow after the freeing of the slaves in 1833. By the turn of the century, it was already a vibrant community made up of former slaves, artisans, traders, and other immigrants, as well as many Malays, brought to South Africa by the Dutch East India Company during its administration of the Cape Colony. With more than 1,700–1,900 families, almost a tenth of Cape Town’s population lived here.

After the Second World War, during the early apartheid era, District Six was relatively cosmopolitan. Situated within sight of the docks, its residents were largely classified as Colored under the Population Registration Act of 1950 and included a significant number of Colored Muslims known as Cape Malays. There were also a number of black Xhosa residents and a smaller number of Afrikaners, English-speaking whites, and Indians.

In the 1960s and 1970s, large slum areas were demolished as part of the apartheid movement, legally defined by the Cape Town Municipality through the Group Areas Act (1950). However, this Act only came into force in 1966 when District Six was declared a whites-only area. New buildings soon emerged from the ashes of the demolished houses and apartments (see District Six Museum, n.d. “About District Six”).

Government officials gave four main reasons for the demolitions. In line with apartheid philosophy, they explained that interaction between the races led to conflict and therefore racial segregation was necessary. They considered District Six to be a slum that should only be cleared, not rebuilt. They also portrayed the area as crime-ridden and dangerous. They claimed that the district was a den of iniquity, full of immoral activities such as gambling, alcohol consumption and prostitution. Although these were the official reasons, most residents believed that the government had targeted the area because of its proximity to the city center, Table Mountain and the harbor (Wikipedia, n.d.).

On October 2, 1964, a ministerial committee appointed by the Minister of Community Development met to investigate the possible re-planning and development of District Six and the adjacent parts of Woodstock and Salt River.

In June 1965, the Secretary announced a 10-year program for the re-planning and development of District Six under CORDA, the Committee for the Rehabilitation of Depressed Areas. On June 12, 1965, all real estate transactions in District Six were frozen. A 10-year ban was imposed on the construction or remodeling of buildings.

On February 11, 1966, the government declared District Six a whites-only area under the Group Areas Act and began resettlement in 1968. Approximately 30,000 people living in the special group area were affected.

In 1966, City Engineer Dr. S.S. Morris put the total population of the affected area at 33,446 people, of whom 31,248 were people of color. But whites made up only one percent of the resident population, colored 94 percent and Indians 4 percent.

The government’s plan for District Six, which was finally presented in 1971, was considered excessive even for the economic boom of the time. On May 24, 1975, part of District Six was declared colored by the Minister of Planning. Most of the approximately 20,000 people who were evicted from their homes were settled in townships in the Cape Flats.

By 1982, more than 60,000 people had been relocated to a township complex about 25 kilometers away of the Cape Flats. The old houses were demolished with bulldozers. The only buildings that remained standing were places of worship. However, international and local pressure made it difficult for the government to redevelop the area. The Cape Technikon (now Cape Peninsula College of Technology) was built on part of District Six, which the government renamed Zonnebloem. Apart from this building and a few police housing units, the area remained undeveloped.

Since the end of apartheid in 1994, the South African government has recognized the former residents’ prior claims to the area and has pledged to help rebuild it. In 2003, work began on the first new buildings: 24 apartments for residents who were over 80 years old (Wikipedia, n.d.).

On February 11, 2004, exactly 38 years after the area was rezoned by the apartheid government, former President Nelson Mandela handed over the keys to the first returning residents. It was expected that around 1,600 families would return over the next three years.

This evolved into the District Six Beneficiary Trust, which was tasked with administering the process by which claimants would get their “land” (effectively their residential space) back. In November 2006, the Trust broke off negotiations with the Cape Town City Council. The Trust accused the City Council (then under a Democratic Alliance (DA) mayor) of delaying the restitution and stated that it preferred to work with the national government, which was controlled by the African National Congress. In response, DA mayor Helen Zille questioned the trust’s right to represent the claimants, stating that it had never been “elected” by the claimants. Some dissatisfied claimants wanted to set up an alternative negotiating body to the Trust. However, due to the historical legacy and “struggle credentials” of most of the Trust’s executives, it was highly likely that the Trust would continue to represent the claimants as it was the principal non-executive director for Nelson Mandela (Wikipedia, n.d.).

performative travelog of a person who speaks as deeply involved in the violent practices of the apartheid system

The District Six Museum

The District Six Museum Foundation was founded in 1989 and the District Six Museum was established in 1994 (see District Six Museum, n.d., “About the District Six Museum”). It serves as a reminder of the events of the apartheid era and the culture and history of the area before the evictions. On the ground floor is a large street map of District Six with handwritten notes from former residents indicating where their homes were located. Other features of the museum include street signs from the old district, depictions of the history and lives of District Six families and historical and documentary explanations of life in the district and its destruction. In addition to its function as a museum, it also serves as a memorial to a decimated community and as a meeting place and community center for Cape Town residents who identify with the history of the district.

Before leaving South Africa in the 1960s, pianist Abdullah Ibrahim lived nearby and visited the area frequently, as did many other Cape jazz musicians. Ibrahim described the District Six to The Guardian as a “hotbed of the jazz explosion, a ‘fantastic city within a city,’ […] where you felt the fist of apartheid it was the valve to release some of that pressure. In the late 50s and 60s, when the regime clamped down, it was still a place where people could mix freely. It attracted musicians, writers, politicians at the forefront of the struggle. We played and everybody would be there.” (Jaggi 2001; Wikipedia, n.d.).

Black South Africans resisted apartheid from the very beginning. In the early 1950s, the African National Congress (ANC) launched a resistance campaign. The aim of this campaign was for black South Africans to violate apartheid laws by entering white areas, using white facilities and refusing to carry “passes” – domestic passes used by the government to restrict the movement of black South Africans within their own country. In response, the government banned the ANC in 1960 and arrested prominent ANC activist Nelson Mandela in August 1962. Mandela was finally released on February 11, 1990, and negotiations to end apartheid officially began that year (Little 2023).

These negotiations lasted four years and ended with Mandela’s election as president in 1994. In 1996, the country established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to address serious human rights violations. A combination of internal and international resistance to apartheid helped to dismantle the white supremacist regime.

Desmond Tutu Memorial Museum

The Old Granary, which houses the Desmond & Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation, has a long history that includes the heavily impacted jurisdiction of the South African colonial era.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu, born 1931, in Klerksdorp, South Africa, was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop of Cape Town from 1986 to 1996. In both cases, he was the first black African to hold this office. He passed away in 2021, in Oasis Care Center, Cape Town, South Africa.

Nomalizo Leah Tutu, born 1930 in Krugersdorp, South Africa, is a South African activist and the widow of Desmond Tutu.

Archbishop Tutu, the founder of the Foundation, is a prime example of unwavering resistance to all social injustices, everywhere, but especially in South Africa. From 1978 to 1985, as Secretary General of the South African Council of Churches, the Archbishop opposed the power of the apartheid state and demanded social and political justice in South Africa. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for this determined but non-violent stance. From 1995 to 2002, the Archbishop chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and listened to harrowing accounts from victims and perpetrators of serious human rights violations and received international recognition for his ability to empathize with the trauma of victims and the remorse of some perpetrators.“The formal end of the apartheid government in South Africa was hard-won. It took decades of activism from both inside and outside the country, as well as international economic pressure, to end the regime that allowed the country’s white minority to subjugate its Black majority. This work culminated in the dismantling of apartheid between 1990 and 1994. On April 27, 1994, the country elected Nelson Mandela, an activist who had spent 27 years in prison for his opposition to apartheid, in its first free presidential election.” (Little 2023)

The white minority that controlled the apartheid government were the Afrikaners — descendants of mostly Dutch colonists who had invaded South Africa since the 17th century. Although the Afrikaner oppression of black South Africans preceded the formal introduction of apartheid in 1948, apartheid legalized and enforced a specific racial ideology that divided South Africans into legally segregated racial groups: Whites, Afrikaners, “Coloreds” (i.e. mixed race) and Indians. The apartheid government violently enforced racial segregation between these groups and forcibly separated many families in which people belonging to different racial categories lived (Little 2023).

From 1948 until the 1990s, a single word dominated life in South Africa. Apartheid — “Afrikaans for ‘apartness’” — kept the country’s black majority under the persistent violence of a small white minority. Racial segregation began in 1948 after the National Party came to power. The party pursued a policy of white supremacy that empowered white South Africans, descendants of Dutch and British settlers, while black Africans were further disenfranchised (History.com Editors 2023).

Pass laws and apartheid policies prohibited blacks from moving to urban areas without immediately finding a job. It was illegal for blacks not to carry a passport book. Blacks were not allowed to marry whites. They were not allowed to start businesses in white areas. From the hospitals to the beaches, all areas were segregated. Education was restricted (History.com Editors 2023).

Racist fears and attitudes towards “natives” characterized white society. Many white women in South Africa learned how to use firearms for self-protection in the event of racial unrest in 1961 when South Africa became a republic (History.com Editors 2023).

Although apartheid was ostensibly intended to allow the different races to develop independently, it forced black South Africans into poverty and hopelessness as they were confined to certain areas. Children from the townships of Langa and Windermere searched for food near Cape Town, for example in 1955.

Although they were subjugated, black South Africans protested against their treatment under apartheid. In the 1950s, the African National Congress, the oldest black political party in the country, initiated a mass mobilization against the racist laws, the so-called Defiance Campaign. Black workers boycotted white businesses, went on strike and staged non-violent protests (Little 2023).

In 1960, the South African police killed 69 peaceful demonstrators in Sharpeville, triggering nationwide protests and a wave of strikes. In response to the protests, the government declared a state of emergency. 30.000 demonstrators marched from Langa to Cape Town in South Africa to demand the release of the black leaders arrested after the Sharpeville massacre (History.com Editors 2023).

Although the demonstrations continued, they were often met with brutality by the police and the state. The state of emergency paved the way for even more apartheid laws.

Some of the demonstrators, fed up with what they saw as ineffective non-violent protests, turned to armed resistance instead. Among them was Nelson Mandela, who helped organize a paramilitary sub-group of the ANC in 1960. He was arrested for treason in 1961 and sentenced to life imprisonment for sabotage in 1964 (History.com Editors 2023).

On June 16, 1976, up to 10,000 black schoolchildren, inspired by new teachings of black consciousness, marched to protest against a new law that forced them to learn Afrikaans in schools. In response, police massacred over 100 protesters and chaos broke out. Despite attempts to contain the protests, they spread throughout South Africa. In response, the movement’s leaders in exile recruited more and more people to join the resistance.

When South African President P.W. Botha resigned in 1989, the deadlock finally broke. Botha’s successor, F.W. de Klerk, decided that it was time to negotiate an end to apartheid. In February 1990, de Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC and other opposition groups and released Mandela. In 1994, Mandela became President of South Africa and South Africa adopted a new constitution that enabled a South Africa free of racial discrimination. It came into force in 1997 (History.com Editors 2023).

At the core of the apartheid system is segregated education.

The Bantu Education Act of 1953, created a separate education system for black South African students and was intended to prepare blacks for a working-class life. In 1959, separate universities were established for black, colored, and Indian students. Hendrik Verwoerd introduced Bantu education into Parliament in 1953. This marked the beginning of the era of apartheid in education. In 1959, the universities were segregated. In 1963, a separate education system was introduced for the “colored people.” Apartheid, which was abolished in 1994, was a system of government in South Africa that systematically segregated groups on the basis of racial classification (New Learning Online, n.d.; Morrow 1990, 174).

In almost every dimension of the comparison, there were and are blatant inequalities between South Africa’s four school systems. When the apartheid government came to power in 1948, it saw the school system as the most important means of propagating its beliefs. Throughout apartheid, schools were one of the clearest symbols of the system. Today, as a new and democratic government seeks to repair and rebuild South Africa’s shattered past, much of its attention is focused on the school system (New Learning Online, n.d.).

The structure of the education system was shaped by the central principle of apartheid, namely a separate school infrastructure for separate groups. In line with the apartheid principle, nineteen ministries of education were established. Each designated ethnic group had its own educational infrastructure. Curriculum development in South African education was strictly controlled from headquarters during apartheid. “While theoretically, at least, each separate department had its own curriculum development and protocols, in reality curriculum formation in South Africa was dominated by committees attached to the white House of Assembly … So prescriptive was this system,” supported by a network of inspectors and subject advisors on the one hand, and several generations of poorly qualified teachers on the other, that authoritarianism, rote learning, and corporal punishment were the norm (New Learning Online, n.d.). These conditions were worsened in the impoverished environments of schools for children of color. Testing criteria and procedures helped to promote the political perspectives of those in power and left teachers with little leeway in setting standards or interpreting their students’ work (New Learning Online, n.d.; see also Gilmore, Soudien, and Donald 1999).

References

District Six Museum. n.d. “About District Six.” Accessed November 14, 2023. https://www.districtsix.co.za/about-district-six/.

District Six Museum. n.d. “About the District Six Museum.” Accessed November 14, 2023.https://www.districtsix.co.za/about-the-district-six-museum/.

Gilmore, David, Crain Soudien, and David Donald. 1999. “Post-apartheid Policy and Practice: Education Reform in South Africa.” In Education in a Global Society: A Comparative Perspective, edited by Mazurek Kas, Margaret Winzer, and Czeslaw Czeslaw Majorek, 341–350. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

History.com Editors. 2023. “Apartheid.” History. Updated April 20, 2023. https://www.history.com/topics/africa/apartheid.

Jaggi, Maya. 2001. “The Guardian Profile: Abdullah Ibrahim.” Guardian, December 8, 2001. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2001/dec/08/jazz.

Little, Becky. 2023. “Key Steps That Led to End of Apartheid.” History. Updated August 22, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/end-apartheid-steps

Morrow, Walter Eugene. 1990. “Aims of Education in South Africa.” International Review of Education / Internationale Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft / Revue Internationale de l’Education 36, no. 2, 171–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3444558.

New Learning Online. n.d. “Apartheid Education.” Accessed November 14, 2023. https://newlearningonline.com/new-learning/chapter-5/supproting-materials/apartheid-education.

South African History Online. n.d. “The Arrival of Jan Van Riebeeck in the Cape – 6 April 1652.” Accessed November 14, 2023. https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/arrival-jan-van-riebeeck-cape-6-april-1652.

South African History Online. n.d. “The Dutch Settlement.” Accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/dutch-settlement.

Wikipedia. n.d. “District Six.” Accessed November 14, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=District_Six&oldid=1184223916.